Find reviews of popular, cool and fun math games, activities and learning resources.

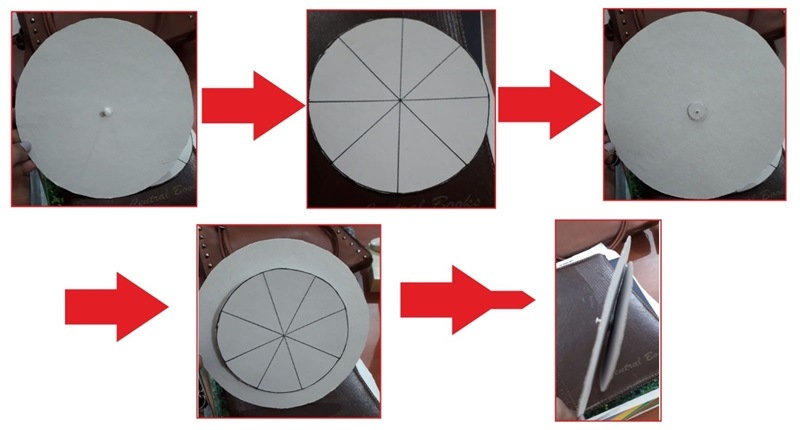

Table spin wheel: Maths activity in school

Table spin wheel is a popular math activity for kids in schools.

GET INSTANT HELP FROM EXPERTS!

- Looking for any kind of help on your academic work (essay, assignment, project)?

- Want us to review, proofread or tidy up your work?

- Want a helping hand so that you can focus on the more important tasks?

Hire us as project guide/assistant. Contact us for more information

Things you need to make a table spin wheel:

- Card board circle cutouts: 8cm, 6cm, 2 cm

- One *Board pin*

- Sketchpen and colour pencils ( to write numbers)

- One small Clay ball ( any color, Any other material for decoration)

- Circle size as below

Dots and Boxes (Game)

Dots and Boxes (also known as Boxes, Squares, Paddocks, Square-it, Dots and Dashes, Dots, Smart Dots, Dot Boxing, or, simply, the Dot Game) is a pencil and paper game for two players (or sometimes, more than two) first published in 1889 by Édouard Lucas.

Game of dots and boxes on the 2×2 board. Starting with an empty grid of dots, players take turns, adding a single horizontal or vertical line between two unjoined adjacent dots.

A player who completes the fourth side of a box earns one point and takes another turn. (The points are typically recorded by placing in the box an identifying mark of the player, such as an initial). The game ends when no more lines can be placed. The winner of the game is the player with the most points.

The board may be of any size. When short on time, 2×2 boxes (created by a square of 9 dots) is good for beginners, and 6×6 is good for experts. In games with an even number of boxes, it is conventional that if the game is tied then the win should be awarded to the second player (this offsets the advantage of going first).

The diagram on the right shows a game being played on the 2×2 board. The second player (B) plays the mirror image of the first player’s move, hoping to divide the board into two pieces and tie the game. The first player (A) makes a sacrifice at move 7; B accepts the sacrifice, getting one box. However, B must now add another line, and connects the center dot to the center-right dot, causing the remaining boxes to be joined together in a chain as shown at the end of move 8. With A’s next move, A gets them all, winning 3–1.

Watch: Dots and Boxes game

At the start of a game, play is more or less random, the only strategy is to avoid adding the third side to any box. This continues until all the remaining (potential) boxes are joined together into chains – groups of one or more adjacent boxes in which any move gives all the boxes in the chain to the opponent.

GET INSTANT HELP FROM EXPERTS!

- Looking for any kind of help on your academic work (essay, assignment, project)?

- Want us to review, proofread or tidy up your work?

- Want a helping hand so that you can focus on the more important tasks?

Hire us as project guide/assistant. Contact us for more information

A novice player faced with a situation like position 1 in the diagram on the left, in which some boxes can be captured, takes all the boxes in the chain, resulting in position 2. But with their last move, they have to open the next (and larger) chain, and the novice loses the game, An experienced player faced with position 1 instead plays the double-cross strategy, taking all but 2 of the boxes in the chain, leaving position 3. This leaves the last two boxes in the chain for their opponent, but then the opponent has to open the next chain. By moving to position 3, player A wins.

The double-cross strategy applies however many long chains there are. Take all but two of the boxes in each chain, but take all the boxes in the last chain. If the chains are long enough then the player will certainly win.

Therefore, when played by experts, Dots and Boxes becomes a battle for control: An expert player tries to force their opponent to start the first long chain. Against a player who doesn’t understand the concept of a sacrifice, the expert simply has to make the correct number of sacrifices to encourage the opponent to hand him the first chain long enough to ensure a win. If the other player also knows to offer sacrifices, the expert also has to manipulate the number of available sacrifices through earlier play. There is never any reason not to accept a sacrifice, as if it is refused, the player who offered it can always take it without penalty.

Thus, the impact of refusing a sacrifice need not be considered in your strategy. Experienced players can avoid the chaining phenomenon by making early moves to split the board. A board split into 4×4 squares is ideal. Dividing limits the size of chains- in the case of 4×4 squares, the longest possible chain is four, filling the larger square.

A board with an even number of spaces will end in a draw (as the number of 4×4 squares will be equal for each player); an odd numbered board will lead to the winner winning by one square (the 4×4 squares and 2×1 half-squares will fall evenly, with one box not incorporated into the pattern falling to the winner). A common alternate ruleset is to require all available boxes be claimed on your turn.

This eliminates the double cross strategy, forcing even the experienced player to take all the boxes, and give his opponent the win. In combinatorial game theory dots and boxes is very close to being an impartial game and many positions can be analyzed using Sprague–Grundy theory. Dots and boxes need not be played on a rectangular grid. It can be played on a triangular grid or a hexagonal grid. Investigations on a triangular variation of the game have even been carried out by Raffles Institution students. There is also a variant in Bolivia when it is played in a Chakana or Inca Cross grid, which adds more complications to the game. Dots-and-boxes has a dual form called “strings-and-coins”.

This game is played on a network of coins (vertices) joined by strings (edges). Players take turns to cut a string. When a cut leaves a coin with no strings, the player pockets the coin and takes another turn. The winner is the player who pockets the most coins. Strings-and-coins can be played on an arbitrary graph. A variant played in Poland allows a player to claim a region of several squares as soon as its boundary is completed.

Sprouts (Math Game)

Sprouts is a pencil-and-paper game with interesting mathematical properties. It was invented by mathematicians John Horton Conway and Michael S. Paterson at Cambridge University in 1967. A 2-spot game of Sprouts The game is played by two players, starting with a few spots drawn on a sheet of paper.

Players take turns, where each turn consists of drawing a line between two spots (or from a spot to itself) and adding a new spot somewhere along the line. The players are constrained by the following rules.

- The line may be straight or curved, but must not touch or cross itself or any other line.

- The new spot cannot be placed on top of one of the endpoints of the new line. Thus the new spot splits the line into two shorter lines.

- No spot may have more than three lines attached to it. For the purposes of this rule, a line from the spot to itself counts as two attached lines and new spots are counted as having two lines already attached to them. In so-called normal play, the player who makes the last move wins.

Watch: Game of Sprouts (Recreational Math)

In misère play, the player who makes the last move loses. The diagram on the right shows a 2-spot game of normal-play Sprouts. After the fourth move, most of the spots are dead–they have three lines attached to them, so they cannot be used as endpoints for a new line.

There are two spots (shown in green) that are still alive, having fewer than three lines attached. However, it is impossible to make another move, because a line from a live spot to itself would make four attachments, and a line from one live spot to the other would cross lines. Therefore, no fifth move is possible, and the first player loses. Live spots at the end of the game are called survivors and play a key role in the analysis of Sprouts. Analysis Suppose that a game starts with n spots and lasts for exactly m moves.

Each spot starts with three lives (opportunities to connect a line) and each move reduces the total number of lives in the game by one (two lives are lost at the ends of the line, but the new spot has one life). So at the end of the game there are 3n−m remaining lives. Each surviving spot has only one life (otherwise there would be another move joining that spot to itself), so there are exactly 3n−m survivors.

There must be at least one survivor, namely the spot added in the final move. So 3n−m ≥ 1; hence a game can last no more than 3n−1 moves. By enumerating all possible moves, one can show that the first player when playing with the best possible strategy will always win in normal-play games starting with n = 3, 4, or 5 spots. The second player wins when n = 0, 1, 2, or 6. At Bell Labs in 1990, David Applegate, Guy Jacobson, and Daniel Sleator used a lot of computer power to push the analysis out to eleven spots in normal play and nine spots in misère play.

Josh Purinton and Roman Khorkov have extended this analysis to sixteen spots in misère play. Julien Lemoine and Simon Viennot have calculated normal play outcomes up to thirty-two spots, plus five more games between thirty-four and forty-seven spots.

They have also announced a result for the seventeen-spot misère game. The normal-play results are all consistent with the pattern observed by Applegate et al. up to eleven spots and conjectured to continue indefinitely, that the first player has a winning strategy when the number of spots divided by six leaves a remainder of three, four, or five. The results for misère play do not follow as simple a pattern: up to seventeen spots, the first player wins in misère Sprouts when the remainder (mod 6) is zero, four, or five, except that the first player wins the one-spot game and loses the four-spot game.

Latin square interactive game

Sets of Latin squares that are orthogonal to each other have found an application as error correcting codes in situations where communication is disturbed by more types of noise than simple white noise, such as when attempting to transmit broadband Internet over power lines.

Watch: Latin Square Interactive Game

Firstly, the message is sent by using several frequencies, or channels, a common method that makes the signal less vulnerable to noise at any one specific frequency. A letter in the message to be sent is encoded by sending a series of signals at different frequencies at successive time intervals. In the example below, the letters A to L are encoded by sending signals at four different frequencies, in four time slots. The letter C for instance, is encoded by first sending at frequency 3, then 4, 1 and 2.

The encoding of the twelve letters are formed from three Latin squares that are orthogonal to each other. Now imagine that there’s added noise in channels 1 and 2 during the whole transmission. The letter A would then be picked up as:

In other words, in the first slot we receive signals from both frequency 1 and frequency 2; while the third slot has signals from frequencies 1, 2 and 3. Because of the noise, we can no longer tell if the first two slots were 1,1 or 1,2 or 2,1 or 2,2. But the 1,2 case is the only one that yields a sequence matching a letter in the above table, the letter A. Similarly, we may imagine a burst of static over all frequencies in the third slot:

Again, we are able to infer from the table of encoding that it must have been the letter A being transmitted. The number of errors this code can spot is one less than the number of time slots. It has also been proved that if the number of frequencies is a prime or a power of a prime, the orthogonal Latin squares produce error detecting codes that are as efficient as possible.

Hexapawn (math / board game)

Hexapawn is a deterministic two-player game invented by Martin Gardner. It is played on a rectangular board of variable size, for example on a 3×3 board or on a chessboard. On a board of size n×m, each player begins with m pawns, one for each square in the row closest to them.

The goal of each player is to advance one of their pawns to the opposite end of the board or to prevent the other player from moving.

Hexapawn on the 3×3 board is a solved game; if both players play well, the first player to move will always lose. Also it seems that any player cannot capture all enemy’s pawns. Indeed, Gardner specifically constructed it as a game with a small game tree, in order to demonstrate how it could be played by a heuristic AI implemented by a mechanical computer. A variant of this game is octapawn.

Watch: HexaPawn game

Rules As in chess, each pawn may be moved in two different ways: it may be moved one square forward, or it may capture a pawn one square diagonally ahead of it. A pawn may not be moved forward if there is a pawn in the next square.

Unlike chess, the first move of a pawn may not advance it by two spaces. A player loses if he/she has no legal moves or the other player reaches the end of the board with a pawn. Dawson’s chess Whenever a player advances a pawn to the penultimate rank (unless it is an isolated pawn) there is a threat to proceed to the final rank by capture.

Zoombinis Logical Journey

This is a captivating game that teaches you how to use rather complex logic and mathematical concepts through a series of mind-bending puzzles-packed epic adventure. Though it is meant for young children, it is an excellent product for almost any age. Some of the skills that you learn include algebraic thinking, data analysis, graphing and mapping, logical reasoning, pattern finding, problem solving, and statistical thinking. Now your kids can develop information-age logic skills that are used in writing computer programs, organizing spreadsheet data, and searching for information on computer networks.

Street smart: Using stones to learn arithmetic

Remember the saying “Where there is a will there is a way”? These street kids seem to be putting that adage to good use.

A Mumbaikar was walking on NM Joshi Marg one morning, when she came across a group of children on the street who were learning something.

A close look revealed that they were actually using stones to learn arithmetic (Math).

Check-out the picture that was shared by reader Bulbul Chaudhary from Lower Parel, Mumbai.

As you can see, when there is a will, you really don’t need a classroom to learn.

GET INSTANT HELP FROM EXPERTS!

- Looking for any kind of help on your academic work (essay, assignment, project)?

- Want us to review, proofread or tidy up your work?

- Want a helping hand so that you can focus on the more important tasks?

StudyMumbai.com is an educational resource for students, parents, and teachers, with special focus on Mumbai. Our staff includes educators with several years of experience. Our mission is to simplify learning and to provide free education. Read more about us.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.